Key takeaways

Grief is a natural reaction to loss that can manifest in both physical and emotional symptoms, and understanding it is crucial for coping and healing.

Anticipatory grief and complicated grief (persistent complex bereavement disorder) represent specific types of grief with distinct causes, symptoms, and risk factors, including those related to COVID-19 deaths.

Grief differs from depression in its cause and emotional focus, and while both can coexist, they require different approaches to management and treatment.

Effective coping with grief involves recognizing its symptoms, understanding the stages of grief, seeking support through counseling or support groups, and eventually finding a way to accept the loss and move forward.

Grief is a natural reaction to loss. When we lose someone close to us, feelings of grief can be powerful, disruptive, and painful.

An understanding of grief, the emotions and actions associated with grief, and the ways in which we can address it, can help us cope with grief and emerge from grieving as a stronger person.

What does grief mean?

Grief refers to emotions and actions that result from experiencing a loss. Grief is primarily associated with the death of a close relative or friend. But we can also feel grief for other people and events.

- Death of important leaders or cultural figures

- Death resulting from traumatic local or international events, like mass shootings or war

- Loss of a friendship or romantic relationship

- Loss of a personal competence or ability, like losing one’s eyesight or not being able to play a favorite sport due to injury

Determining an exact definition of grief is less important than recognizing grief and working to manage it. “When grief is unattended to, it does not and cannot heal itself,” says Grief Educator Karen Nicola, MA.

What is anticipatory grief?

Anticipatory grief is usually associated with mourning for a loved one who has been diagnosed with a terminal disease.

“We begin mourning losing our loved one, when we realize we are going to lose them in the foreseeable future,” says Leila Levinson, LMSW, a counselor at Just Mind, LLC. “The diagnosis forces us to begin envisioning our life without them.”

Levinson notes that terminal illness in a loved one is not the only cause of anticipatory grief. We might experience anticipatory grief as we approach major life changes like a child leaving home, or being unable to drive.

What is complicated grief?

Complicated grief, now known as persistent complex bereavement disorder, is characterized by overwhelming, intense, and prolonged grief. A 2011 study estimated that approximately 1 in 15 people (6.7%) experience complicated grief after a major bereavement such as the loss of a family member.

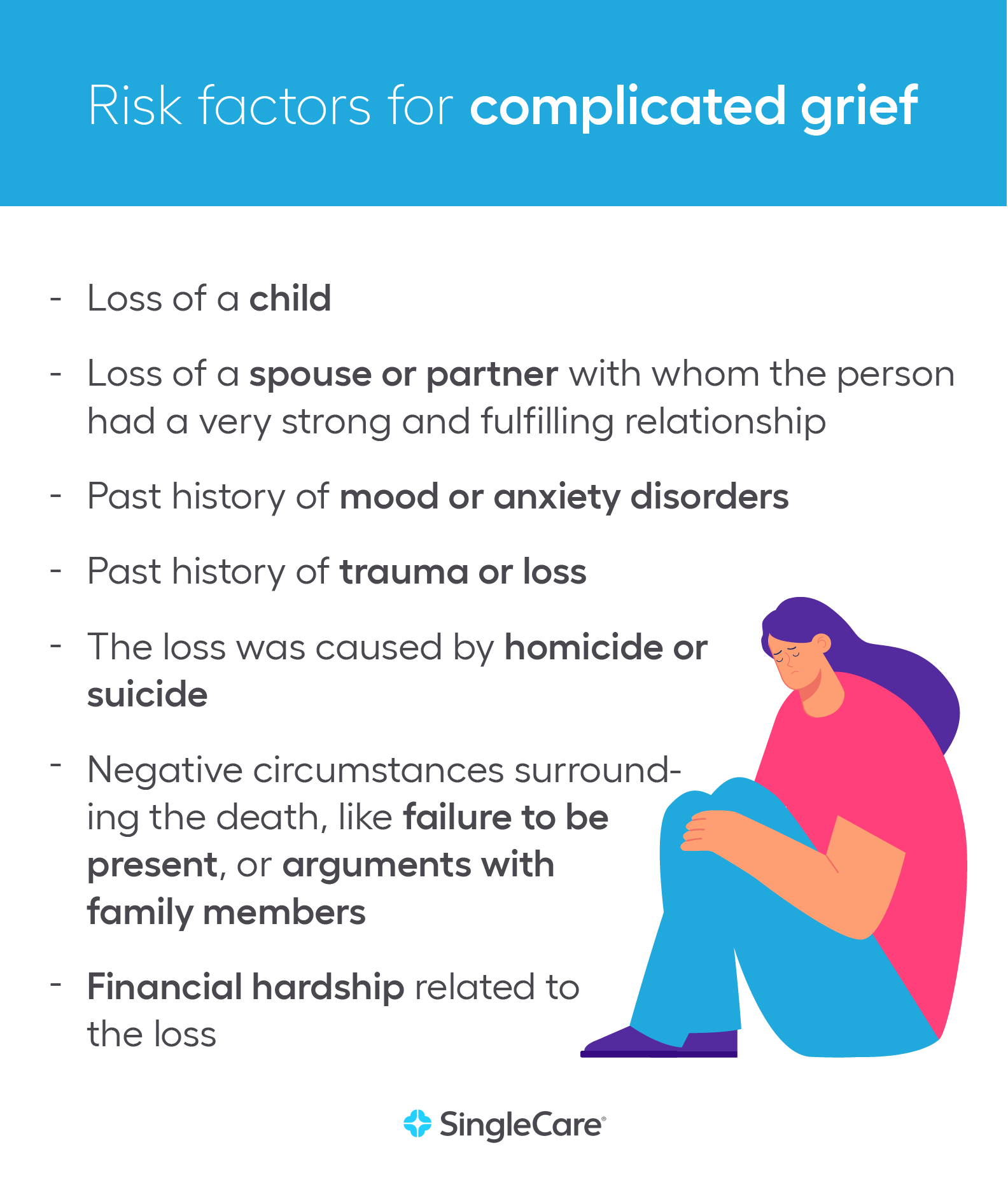

Risk factors for complicated grief

- Loss of a child

- Loss of a spouse, partner, or anyone with whom the person had a very strong and fulfilling relationship

- History of mood or anxiety disorders

- History of trauma or loss

- The loss was caused by homicide or suicide

- Negative circumstances surrounding the death, like failure to be present, or arguments with family members

- Financial hardship related to the loss

Recent studies have noted an increased risk of complicated grief among those who have lost loved ones to COVID-19, and include key complicated grief risk factors related to COVID-19 deaths.

- Sudden, unexpected, seemingly preventable, and random deaths

- The infected person dying alone or being unable to visit them

- Inability to conduct a typical, in-person funeral due to restrictions on large gatherings

Grief vs. depression

Grief and depression are different. Grief is a normal process that can usually be coped with over time without medication. Depression is typically more prolonged and characterized by persistent feelings of worthlessness or guilt unrelated to grief. Depression is also a disorder that is often treated with medication.

“Positive emotions occur as frequently as negative ones as early as a week after a loved one dies,” writes M. Katherine Shear, MD. “Depression biases thinking in a negative direction. Grief does not.”

Complicated grief is usually accompanied by signs and symptoms such as intense longing to be around the loved one again, feelings of guilt surrounding their death, or avoidance of activities that once were shared with that person.

Depression is more self-directed than grief. Someone with depression may not be experiencing intense longing for something or someone. They often feel negative thoughts about themselves, rather than others. Someone experiencing depression will also tend to withdraw from all activities, not just the ones associated with someone they have lost.

Complicated grief can develop into depression, or can be present at the same time as depression.

What are the symptoms of grief?

Grief can manifest in many ways. As a normal process, grief can cause mild physical and emotional symptoms that resolve with time. Symptoms associated with complicated grief, however, may require intervention.

The symptoms below are common among people dealing with grief, but not everyone experiences them. Every person’s experience of grief is different.

Physical symptoms of normal grief

- Trouble sleeping

- Sleeping too much

- Low energy levels

- Loss of appetite or weight loss

- Weakness

- Stomach pain

- Nausea

- Chest pain

- Muscle aches

Emotional symptoms of normal grief

- Feeling shock or distress

- Experiencing disbelief and denial

- Feeling restless or anxious

- Feeling angry

- Feeling sad

- Avoiding social interactions

- Becoming preoccupied with death

- Suggesting reasons for the death that don’t make sense to others

- Ruminating over specific mistakes or ways they disappointed the deceased, whether real or imagined

- Feeling personally responsible for the death

- Feeling envy when seeing others with their (still-living) loved ones

Emotional symptoms of complicated grief

Note: Some of these symptoms are similar to normal grief. When these feelings last longer than one month, they may be a sign of complicated grief.

- Feeling alone, detached, or distrustful of others since the death

- Having trouble pursuing interests or planning for the future after the death of the loved one

- Feeling unable to enjoy life, feeling that life is meaningless or empty

- Loss of identity or purpose in life, feeling like part of themselves died with the loved one

- Intense yearning or longing for the person who died

- Intense feelings of loneliness or that life is meaningless without the person

- Thoughts of joining the deceased in death, because life isn’t worth living without them

- Feelings of being shocked or emotionally numb that persist longer than one month

- Persistent unreasonable thoughts about the circumstances of the person’s death

- Feelings of anger or bitterness related to the death

What are the stages of grief?

The classic five stages of grief are denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. These stages were proposed in the late 1960s by psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross. Originally, Kübler-Ross identified the stages from her work with terminally ill patients coping with grief. Later on, the stages began to be applied to those grieving the deaths of others.

Today, some grief counselors question the helpfulness and accuracy of the five stages model. Other grief stage models have emerged, such as Therese Rando’s model of the six “R” processes of mourning: recognize, react, recollect, relinquish, readjust, and reinvest.

“Inherent in all (grief stages) is the centrality of grief work: The active search of the bereaved for a way to understand their loss and how it has changed their life, and to find signs that will enable them to create a new normal,” says Levinson.

Counselors emphasize that grief rarely progresses neatly from one stage to the next. Stages are skipped, or returned to. Some last longer than others.

“This grief work occurs over an extended period of time that will vary with every person,” says Levinson. “The pain of grief often springs up unexpectedly or is predictable, coming intensely at birthdays or holidays.”

“Although grief is described in phases or stages, it may feel more like a roller coaster, with ups and downs,” notes the American Cancer Society in its guide to grief.

Dealing with grief

Grief is a normal process. We should expect ourselves and others to feel strong emotions during a period of bereavement.

Decades of research and observation have led psychiatrists to the conclusion that suppressing grief is unhealthy. But research also shows that obsessing over grief isn’t healthy either.

“The ideal is to achieve a balance between avoidance and confrontation, which enables the person gradually to come to terms with the loss,” writes psychiatrist Colin Murray Parkes.

When to seek help for grief

Counseling can be an important part of coping with major life events like a divorce or career change. It can help with grief, too. Seeking out a grief counselor can be thought of as a preventative care measure. There is nothing wrong in coping with grief on your own or with the help of friends and family.

There is no standardized timeline for how long grief should last. Some people start to feel better within several weeks. However, periods of grief can last for six months to a year or longer. If strong feelings of grief persist beyond a year and start to greatly interfere with daily life, it may be wise to seek help from a healthcare professional.

How to help loved ones with grief

The type of support that bereaved people need often changes over time.

In the immediate aftermath of a loss, providing simple comfort is best. “Newly bereaved people … will respond best to the kind of support that is normally given by a parent,” writes Parkes. “A touch or a hug will often do more to facilitate grieving than any words.”

Over the next few weeks, the bereaved need reassurance about their feelings and actions. It can help to share a cry with them, validating that their sadness is normal. The bereaved may have feelings of guilt about withdrawing from activities or responsibilities. They need to know that this is okay.

As time goes on, the situation can reverse. As the surviving loved one begins to resume a more normal life, they may feel guilty that they have not grieved enough. They may need to feel that they have permission from close friends and family to begin enjoying life again.

Grief counseling

Grief counseling is a process that can be helpful to anyone dealing with grief. Counseling can be ongoing, or it can last for one session.

In a typical session, a counselor might ask about the relationship between the patient and the person they have lost. They might ask how life has changed since the bereavement, and what emotions they are feeling.

The counselor is likely to suggest coping strategies that may help the person successfully work through grief. Just talking openly about grief with a counselor can be a coping mechanism in itself.

Grief therapy

Compared to grief counseling, grief therapy is a more involved process. Grief therapy will usually occur over multiple sessions, and involve specific treatments recommended by a licensed therapist, counselor, or psychiatrist. In some cases, medications may be prescribed, such as antidepressants, anxiety medications, or sleep aids.

People experiencing grief alongside other mental health disorders, like depression, anxiety, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), may benefit from grief therapy.

Grief support groups

Sharing the experience of grief with others can be a powerful coping mechanism.

Hearing the stories of others can help to validate the strong emotions felt by those who are grieving. A grief support group can also serve as a welcome break in the day, and something to look forward to. Everyone grieves differently, and hearing the coping mechanisms of others may provide those who are grieving with coping ideas to try for themselves.

The traditional support group usually consists of a regular in-person meeting, perhaps at a local community center. But grief support groups can take many forms. Grief groups can exist on social media platforms, such as online bulletin boards or online chats, and they can include people from all over the world. Online grief groups can also be more specialized than a local, in-person group. For example, Facebook has a grief support group for People in Their 20s & 30s Who Have Lost a Parent.

Accepting grief can build strength

Losing parents and other loved ones is a natural part of life. The grief that follows is a test of one’s personal ability to cope and the strength of their support systems. Psychiatrists say that once a bereaved person has worked through their grief and accepted the loss, they often emerge from the experience with newfound resilience, and even with a more positive outlook on life.

“Acceptance is the greatest honor we can give to the one we lost,” concludes Levinson. “In our acceptance we say: You were precious; life will never be the same; and I commit myself to create the full life you would want for me.”